Once a model is trained with its parameters adjusted, it can be deployed. The model is made available in a production environment to make predictions on new, unseen data, fed as input to the trained model. This could be on a server in a Jupyter Notebook, a cloud platform, a mobile app, or any system where real-time or batch predictions are needed based on the model.

Why Do We Use Neurons?

Individual neurons’ simplicity and adaptability make them incredibly powerful when combined in layers to form neural networks. One of the most remarkable properties of neural networks is their ability to serve as “universal approximators.” Theoretically, a neural network (even with a single hidden layer, given enough neurons) can approximate any continuous function to a desired level of accuracy. In other words, they can model and represent a vast range of intricate patterns, behaviors, and relationships in data.

The concept of universal approximation underscores the potential and versatility of neural networks. By adjusting the weights and biases during training, a neural network doesn’t just adapt—it can model complex, non-linear relationships in the data, making it a tool of choice for numerous applications ranging from image recognition to financial forecasting.

While the theory assures us of this capability, creating and training such networks efficiently for complex tasks in practice often requires deeper architectures (deep learning) and sophisticated training techniques.

The Perceptron

As we mentioned in our Getting Started with AI course, the perceptron was developed by Frank Rosenblatt in the late 1950s and is one of the simplest forms of a neural network. It can be considered the building block or the “atom” of more complex neural networks. It’s essentially a single-layer neural network. Functionally, perceptrons work as binary classifiers, meaning they can categorize inputs into one of two classes. This is because, with a single neuron, perceptrons can’t handle data that can’t be separated by a single straight line (or hyperplane in higher dimensions). This limitation in network capacity inspired the creation of linking perceptrons together, creating networks… Neural networks! In this module’s exercise, we will create our own perceptron and take it for a spin!

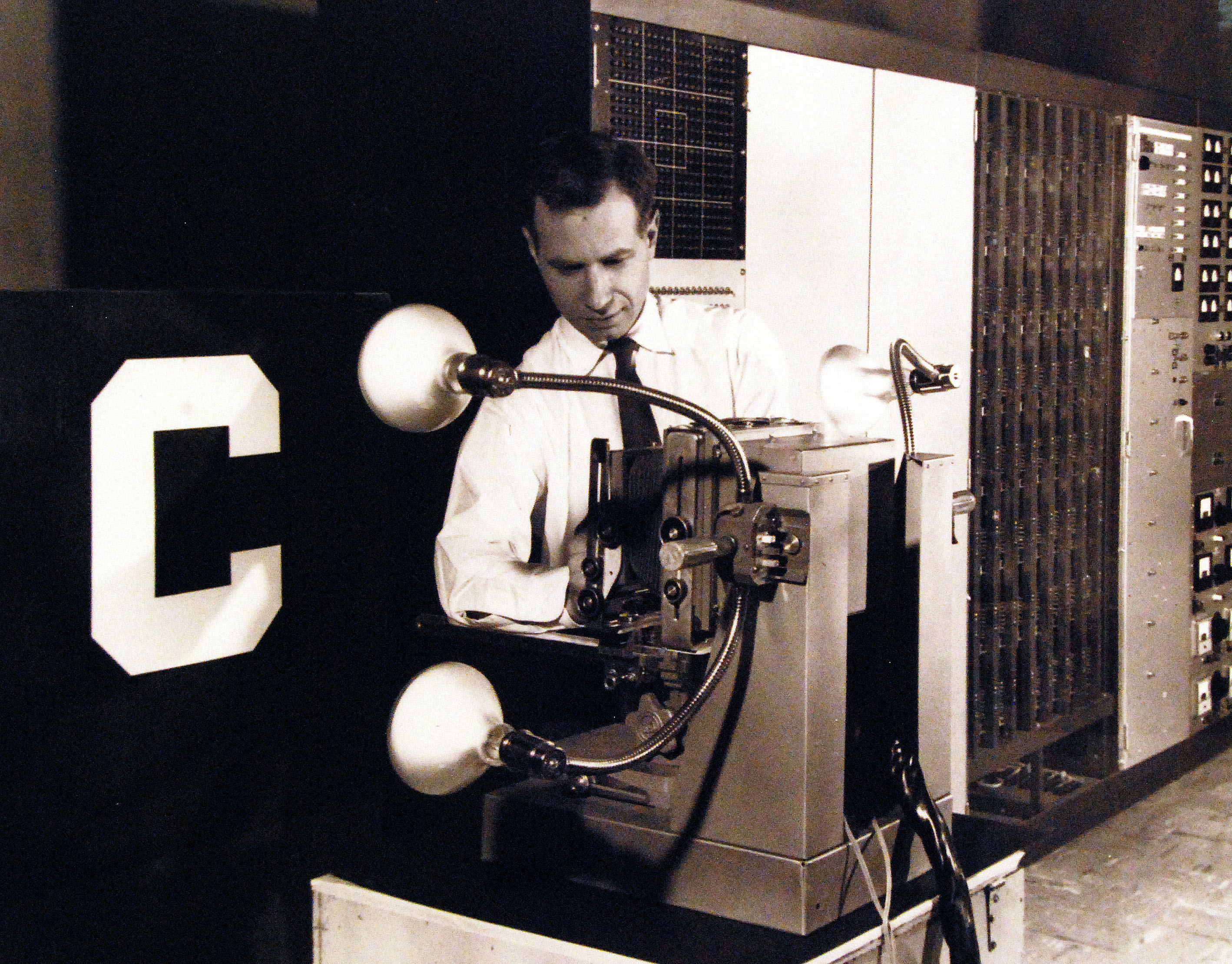

From Wikimedia Commons: This photo shows the Mark I Perceptron, an experimental machine which can be trained to automatically identify objects or patterns, such as letters of the alphabet. Originated by Dr. Frank Rosenblatt, a psychologist who is in charge of the program at Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, Buffalo, New York, Mark I is an electromechanical device consisting basically of a “sensory unit” of photocells which contain the machine’s memory, and response units which visually display the machine’s pattern recognition response. The machine is generally trained by placing the test patterns, which could be letters of the alphabet of a single-type face, in the view field of the perceptron’s photoelectric cell “eye.” When the machine incorrectly identifies a pattern or letter, the trainer forces it to respond correctly by means of an electrical control. When the training is completed the letters of the particular type face can then be shown to the machine’s eye, and it will correctly identify the letters without error. When the recognition problem has been complicated by adding letters of a different type face, the machine has been correct 85 percent of the time. The perceptron has particular potential use in the processing of non-numerical information for the solution of scientific, engineering, and military problems. The perceptron research program is sponsored by the Office of Naval Research with the assistance from Rome Air Development Center, Rome, New York, of the Air Research and Development Command. Photograph released June 24, 1960.

From Wikimedia Commons: This photo shows the Mark I Perceptron, an experimental machine which can be trained to automatically identify objects or patterns, such as letters of the alphabet. Originated by Dr. Frank Rosenblatt, a psychologist who is in charge of the program at Cornell Aeronautical Laboratory, Buffalo, New York, Mark I is an electromechanical device consisting basically of a “sensory unit” of photocells which contain the machine’s memory, and response units which visually display the machine’s pattern recognition response. The machine is generally trained by placing the test patterns, which could be letters of the alphabet of a single-type face, in the view field of the perceptron’s photoelectric cell “eye.” When the machine incorrectly identifies a pattern or letter, the trainer forces it to respond correctly by means of an electrical control. When the training is completed the letters of the particular type face can then be shown to the machine’s eye, and it will correctly identify the letters without error. When the recognition problem has been complicated by adding letters of a different type face, the machine has been correct 85 percent of the time. The perceptron has particular potential use in the processing of non-numerical information for the solution of scientific, engineering, and military problems. The perceptron research program is sponsored by the Office of Naval Research with the assistance from Rome Air Development Center, Rome, New York, of the Air Research and Development Command. Photograph released June 24, 1960.